When I was a child, during Physical Education (PE) at school, we would often have to play brännboll, a game similar to rounders.

I was never very athletic and still wear the thumb-sized scar on my right knee from a game where an attempt to catch the ball ended with ruined clothes as I skid across the tarmac, grating my jeans and knee open.

Why we played on tarmac instead of grass is beyond me.

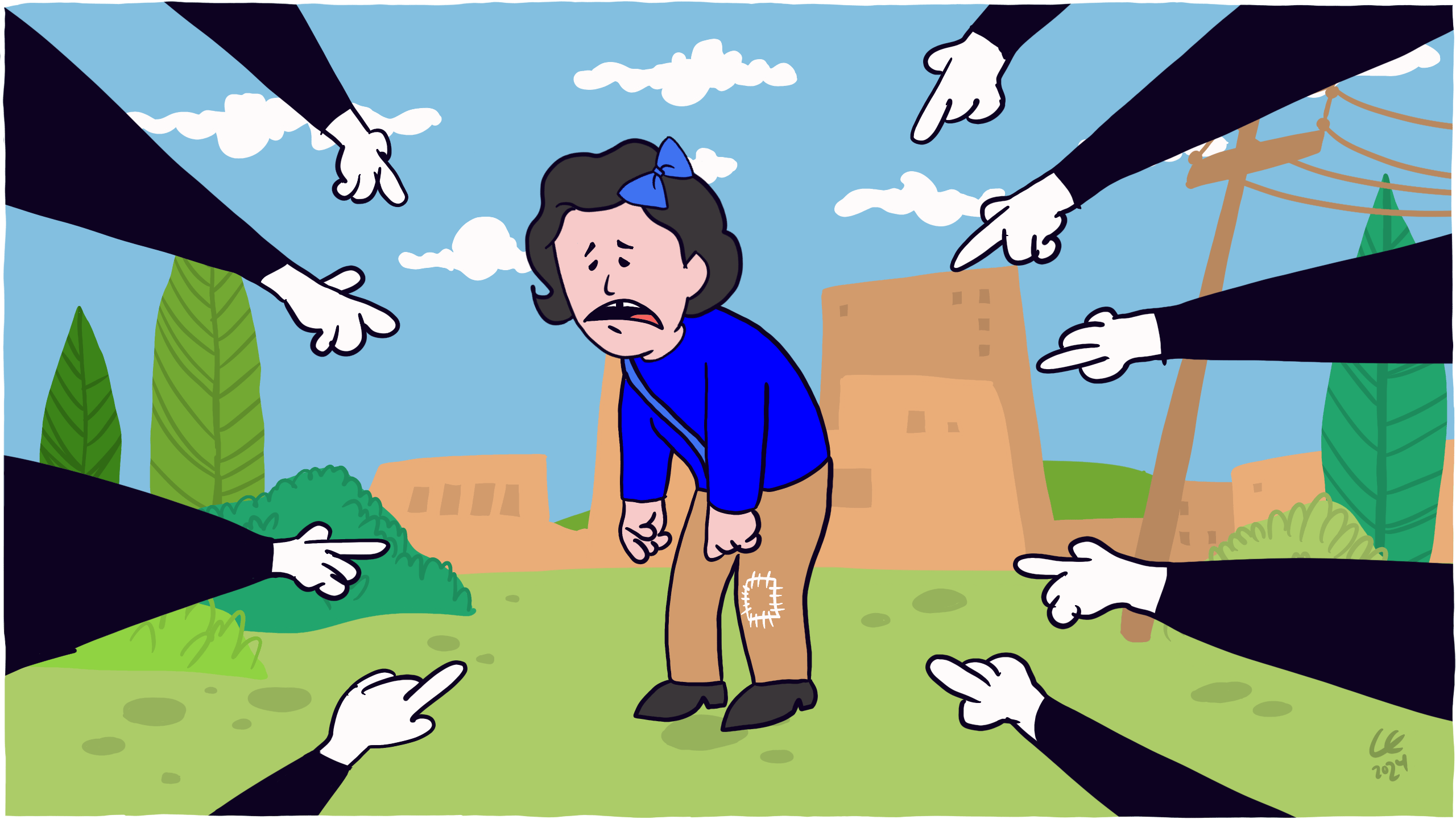

Short and unathletic, I was always one of the students who were picked last for brännboll, if I was chosen at all.

There’s no choice to be had any more when you’re the last one.

It made me feel like I wasn’t good enough, or that I didn’t belong. I felt excluded.

It’s not a nice feeling, is it?

From not being welcomed to play sports during P.E. to not getting invited to that company meeting, exclusion is something we can all relate to on some level.

And despite the personal rejection we feel, the act of exclusion often isn’t personal, it’s systemic.

It’s a very real and compounding, intersectional system of oppression and exclusion.

Let’s look at the result of the compounding effects of this exclusion.

The compounding effects of exclusion

There are about 7.53 billion people on this planet of ours.

But through a difference in position, power and privilege, not everyone gets to play this game of life’s brännboll.

As Caroline Criado-Pérez shows in her book Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men—patriarchy doesn’t just exclude all women from all of its products and services, it ignores them in the thoughts process itself.

She illustrates this in numerous examples but one which stands out is the automotive industry.

Criado-Pérez shows that when women are involved in a car crash, “they are 47% more likely to be seriously injured than a man, and 71% more likely to be moderately injured, even when controlling for factors such as height, weight, seat-belt usage, and crash intensity.”

Because cars haven’t been designed for women.

And neither has technology.

Technology ignores women in equally painful measures, made no more apparent than by the lack of simple things such as period tracking in the Apple Watch—a feature which after over four years is only just due for release.

Technology excludes all women, and the reality of exclusion is that we’re now left with 3.79 billion men on this planet of ours.

We aren’t just excluding women though, we’re also excluding people over 40, as a recent WebAIM study revealed.

As we age, our eyes’ ability to focus decreases and we begin to struggle to read small print or low contrast text.

The WebAIM study showed that the most common issue on the web is a lack of colour contrast.

Now, we’re left with 2.48 billion men between the age of 0-39.

We’ll carry on excluding people with all the data we have—keep in mind, the available data is sometimes incomplete or even non-existent—something Criado-Pérez also talks about.

Let’s exclude young people—now there are 1.17 billion left—and people with permanent disabilities—now there are 1 billion left.

And people with dyslexia—now there are 939 million left—and those who don’t speak English as their first language—now there are 61 million left.

This is also the point where I’m no longer included.

And finally, let’s exclude people of color—now there are 32 million left—and people who are gay.

Now, who’s left?

After excluding large demographics, we’re now left with approximately 29 million men. Men between the age of 20-39 who are able-bodied, neurotypical, white, heterosexual and speak English as their first language.

These privileged few, aren’t just deciding everything about where technology is going but also who are shaping it.

Reshaping the world

To change this requires challenging the dominant social, political and cultural system—which is white supremacist capitalist patriarchy—not just by building for a wider audience, but by assembling a team which represents that audience and beyond.

Because whilst, during those games of brännboll I was on the receiving side of exclusion, the reality is that in most circumstances I am on the other side. I meet almost all of the criteria for people who benefit the most from the current system of oppression and exclusion.

Through silence and inaction, we are complicit and letting it flourish.

If we don’t speak up and fight against white supremacist capitalist patriarchy and exclusion, someone else will speak for us, and we might not like what they have to say.

And instead of inviting marginalised people to play our game of brännboll, what we really need to do is let the people who have been excluded decide what game it should be.

We need to let their voices guide the future shape of inclusion.

Even if that means, being excluded.

Know someone who would benefit from this article? Share it with them.