“Hey Google,” my partner said to our smart speaker.

No response.

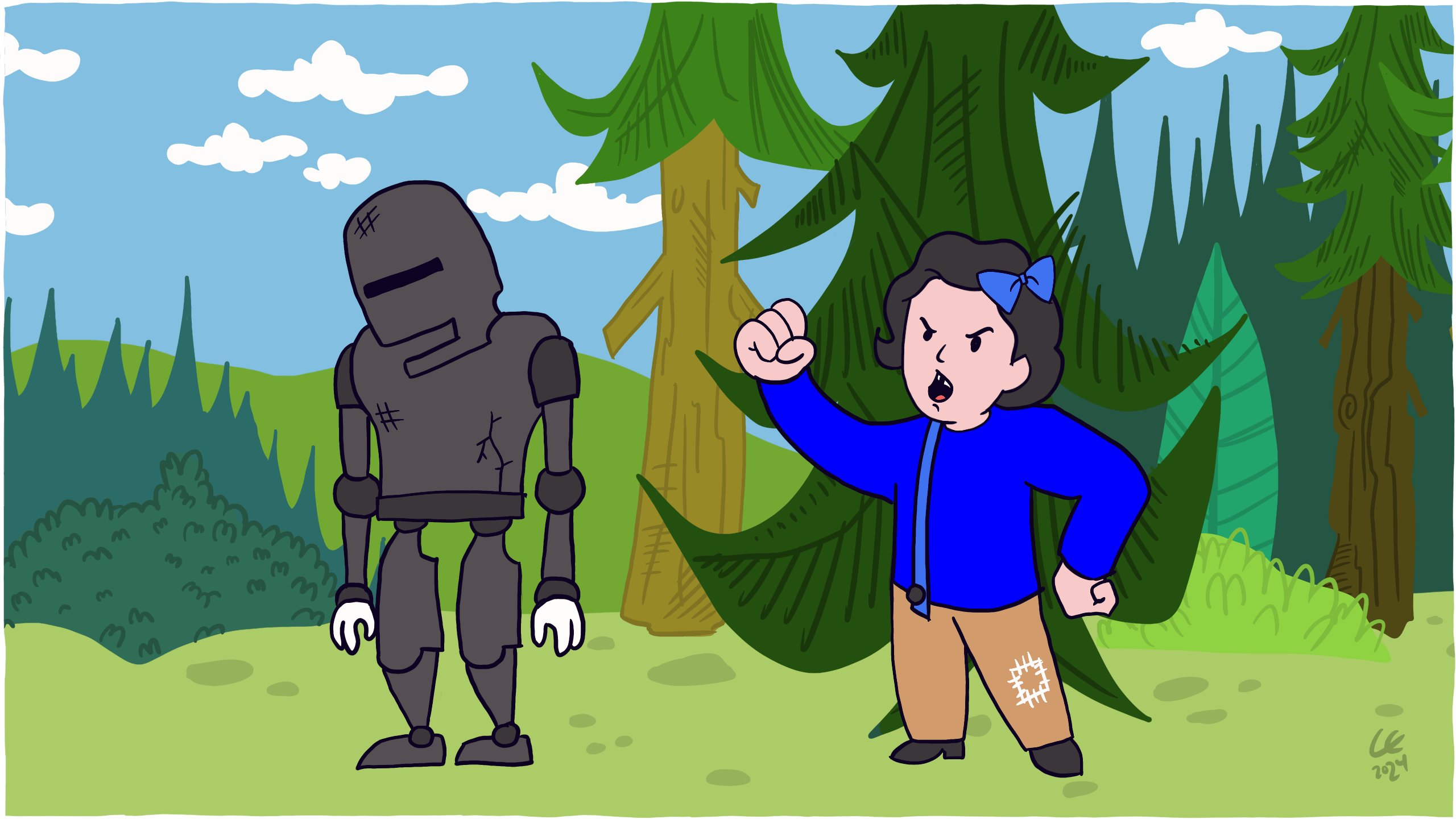

The Google Home stonewalled her.

Raising her voice and without inflection, she repeated, “Hey Google,” as her frustration grew.

After three more attempts, I suggested that she try lowering the pitch of her voice and make her best attempt to sound like a news broadcaster.

“Blip,” replied the smart speaker in an instant.

At this point, we had both forgotten why she was talking to the digital assistant in the first place.

The result shouldn’t surprise us, considering voice recognition software hasn’t been trained to listen to women. Or people with any accents which aren’t American English.

And she happens to be both.

Ironically, Google isn’t even the worst offender.

One study that looked at Alexa (Amazon’s smart speaker) found that the smart speaker misunderstood speech from people with non-native English accents 30% more than from those with native accents.

Meanwhile, the vice president of voice technology at car navigation system supplier ATX, Tom Schalk, thinks women should submit to lengthy training to fix the so-called issues with their voices.

What issues is he referring to?

“Not sounding like men.”

In reality, studies show that men have higher rates of disfluency, produce words with slightly shorter durations and use more alternate ‘sloppy’ pronunciations.

Overall, women’s speech is significantly more intelligibility, and voice technology would be able to understand women with less training than it needed to understand men.

Now imagine what it’s like for anyone with a speech disorder, such as aphasia.

Aphasia affects a person’s ability to understand, speak, read, write and use numbers.

Between 25–55% of stroke survivors experience aphasia. It impacts their ability to communicate, not their intelligence.

As the technology develops and voice user interfaces become more prominent in our everyday lives, we must design them with people with speech disorders.

Because when we communicate in real life, we can use body language and tonality to make sense of inconsistencies and contradictory sentences.

But for user interfaces that rely on voice, understanding all the necessary context is next to impossible in the brief interactions we have.

Take action

The main takeaway is to not design products and services which rely exclusively on voice input to work.

Instead, provide alternative ways of interaction for people.

As for designing clear and conversational content, here’s some practical advice:

- Don’t use complicated words or figures of speech, instead speak in the simplest form your language allows

- Don’t make people guess the phrases, instead provide them with examples of what they can do

- Don’t rely on auditory feedback only, instead use visual and tactile feedback wherever possible

- Don’t make people listen to a long list of options, instead limit the amount of information

- Don’t rely on exact phrases, instead let people use synonyms

- Don’t make complex menus, instead allow for non-linear, natural conversations

Voice technology is getting to the point where it can empower people to live independent lives in a way that might not have been possible 10 years ago.

But that power comes the potential for exclusion and it should not be taken lightly.

The reality is that we all have circumstances when our speech is impaired; From being non-verbal to having Laryngitis, or a heavy-accent when speaking a non-native language.

The solutions we create for one group of people always help all groups of all people.

Nowadays, my partner and I often avoid using the Google Home assistant.

If only someone had trained it using women’s voices.

Or people with accents.

Or both.

Know someone who would benefit from this article? Share it with them.